Say Cheese and Die--Again!

Say Cheese and Die--Again! Fifth-Grade Zombies

Fifth-Grade Zombies Revenge of the Invisible Boy

Revenge of the Invisible Boy The Dummy Meets the Mummy!

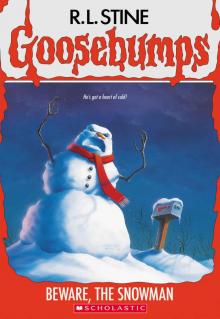

The Dummy Meets the Mummy! Beware, the Snowman

Beware, the Snowman Welcome to Smellville

Welcome to Smellville Camp Daze

Camp Daze Calling All Creeps

Calling All Creeps Missing

Missing How I Learned to Fly

How I Learned to Fly I Live In Your Basement

I Live In Your Basement Ghost Camp

Ghost Camp Chicken Chicken

Chicken Chicken My Friend Slappy

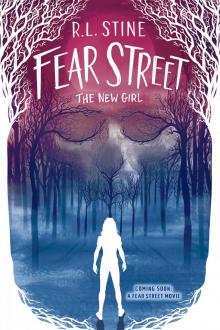

My Friend Slappy The New Girl

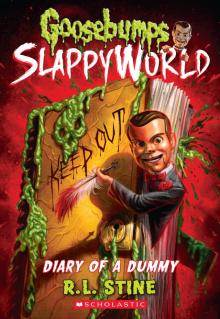

The New Girl Diary of a Dummy

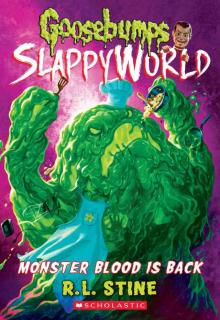

Diary of a Dummy Monster Blood is Back

Monster Blood is Back Beware, The Snowman (Goosebumps #51)

Beware, The Snowman (Goosebumps #51) Give Yourself Goosebumps: Beware of the Purple Peanut Butter

Give Yourself Goosebumps: Beware of the Purple Peanut Butter Drop Dead Gorgeous

Drop Dead Gorgeous Claws!

Claws! 61 - I Live in Your Basement

61 - I Live in Your Basement Shadow Girl

Shadow Girl 14 - The Werewolf of Fever Swamp

14 - The Werewolf of Fever Swamp You Can't Scare Me!

You Can't Scare Me! The Sign of Fear

The Sign of Fear Red Rain

Red Rain The Horror at Chiller House

The Horror at Chiller House Welcome to Dead House

Welcome to Dead House What Holly Heard

What Holly Heard Have You Met My Ghoulfriend?

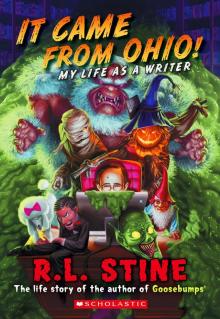

Have You Met My Ghoulfriend? It Came From Ohio!

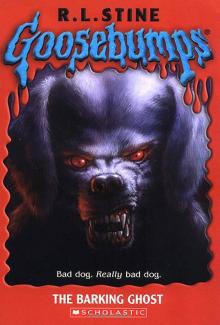

It Came From Ohio! The Barking Ghost g-32

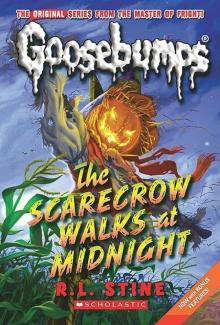

The Barking Ghost g-32 20 - The Scarecrow Walks at Midnight

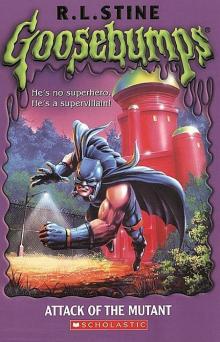

20 - The Scarecrow Walks at Midnight 25 - Attack of the Mutant

25 - Attack of the Mutant Vampire Breath

Vampire Breath Please Do Not Feed the Weirdo

Please Do Not Feed the Weirdo![[Goosebumps 12] - Be Careful What You Wish For... Read online](//i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/12/[goosebumps_12]_-_be_careful_what_you_wish_for__preview.jpg) [Goosebumps 12] - Be Careful What You Wish For...

[Goosebumps 12] - Be Careful What You Wish For... Fear Games

Fear Games Red Rain: A Novel

Red Rain: A Novel Night of the Living Dummy 3

Night of the Living Dummy 3 Werewolf Skin

Werewolf Skin Curse of the Mummy's Tomb

Curse of the Mummy's Tomb![[Goosebumps 37] - The Headless Ghost Read online](//i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/17/[goosebumps_37]_-_the_headless_ghost_preview.jpg) [Goosebumps 37] - The Headless Ghost

[Goosebumps 37] - The Headless Ghost Escape from Camp Run-For-Your-Life

Escape from Camp Run-For-Your-Life Diary of a Mad Mummy

Diary of a Mad Mummy Little Comic Shop of Horrors

Little Comic Shop of Horrors My Name Is Evil

My Name Is Evil The Rottenest Angel

The Rottenest Angel Monster Blood For Breakfast!

Monster Blood For Breakfast!![[Goosebumps 41] - Bad Hare Day Read online](//i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/16/[goosebumps_41]_-_bad_hare_day_preview.jpg) [Goosebumps 41] - Bad Hare Day

[Goosebumps 41] - Bad Hare Day The Adventures of Shrinkman

The Adventures of Shrinkman House of Whispers

House of Whispers The Taste of Night

The Taste of Night Say Cheese and Die!

Say Cheese and Die! Wanted

Wanted One Day at Horrorland

One Day at Horrorland Scream and Scream Again!

Scream and Scream Again! Haunted Mask II

Haunted Mask II![[Goosebumps 03] - Monster Blood Read online](//i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/16/[goosebumps_03]_-_monster_blood_preview.jpg) [Goosebumps 03] - Monster Blood

[Goosebumps 03] - Monster Blood Tick Tock, You're Dead!

Tick Tock, You're Dead! Lose, Team, Lose!

Lose, Team, Lose! Night of the Puppet People

Night of the Puppet People The Boy Who Ate Fear Street

The Boy Who Ate Fear Street The Birthday Party of No Return!

The Birthday Party of No Return! Toy Terror

Toy Terror![[Goosebumps 27] - A Night in Terror Tower Read online](//i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/16/[goosebumps_27]_-_a_night_in_terror_tower_preview.jpg) [Goosebumps 27] - A Night in Terror Tower

[Goosebumps 27] - A Night in Terror Tower![[Goosebumps 39] - How I Got My Shrunken Head Read online](//i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/16/[goosebumps_39]_-_how_i_got_my_shrunken_head_preview.jpg) [Goosebumps 39] - How I Got My Shrunken Head

[Goosebumps 39] - How I Got My Shrunken Head 17 - Why I'm Afraid of Bees

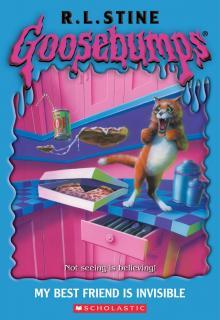

17 - Why I'm Afraid of Bees![[Goosebumps 57] - My Best Friend is Invisible Read online](//i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/16/[goosebumps_57]_-_my_best_friend_is_invisible_preview.jpg) [Goosebumps 57] - My Best Friend is Invisible

[Goosebumps 57] - My Best Friend is Invisible They Call Me the Night Howler!

They Call Me the Night Howler! House of a Thousand Screams

House of a Thousand Screams The Curse of Camp Cold Lake

The Curse of Camp Cold Lake Mostly Ghostly Freaks and Shrieks

Mostly Ghostly Freaks and Shrieks Dangerous Girls

Dangerous Girls 30 - It Came from Beneath the Sink

30 - It Came from Beneath the Sink Killer's Kiss

Killer's Kiss Attack of the Graveyard Ghouls

Attack of the Graveyard Ghouls 62 - Monster Blood IV

62 - Monster Blood IV Double Date

Double Date The Secret Bedroom

The Secret Bedroom![[Goosebumps 48] - Attack of the Jack-O'-Lanterns Read online](//i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/17/[goosebumps_48]_-_attack_of_the_jack-o-lanterns_preview.jpg) [Goosebumps 48] - Attack of the Jack-O'-Lanterns

[Goosebumps 48] - Attack of the Jack-O'-Lanterns![[Goosebumps 26] - My Hairiest Adventure Read online](//i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/17/[goosebumps_26]_-_my_hairiest_adventure_preview.jpg) [Goosebumps 26] - My Hairiest Adventure

[Goosebumps 26] - My Hairiest Adventure 50 - Calling All Creeps!

50 - Calling All Creeps! The Hidden Evil

The Hidden Evil I Am Slappy's Evil Twin

I Am Slappy's Evil Twin Planet of the Lawn Gnomes

Planet of the Lawn Gnomes Piano Lessons Can Be Murder

Piano Lessons Can Be Murder Let's Get Invisible!

Let's Get Invisible! Why I Quit Zombie School

Why I Quit Zombie School Bride of the Living Dummy

Bride of the Living Dummy 03 - Monster Blood

03 - Monster Blood The Attack of the Aqua Apes

The Attack of the Aqua Apes![[Goosebumps 15] - You Can't Scare Me! Read online](//i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/13/[goosebumps_15]_-_you_cant_scare_me_preview.jpg) [Goosebumps 15] - You Can't Scare Me!

[Goosebumps 15] - You Can't Scare Me! Goosebumps the Movie

Goosebumps the Movie The New Girl (Fear Street)

The New Girl (Fear Street) 21 - Go Eat Worms!

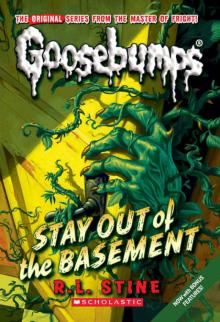

21 - Go Eat Worms! 02 - Stay Out of the Basement

02 - Stay Out of the Basement The Second Horror

The Second Horror Scare School

Scare School Beware!

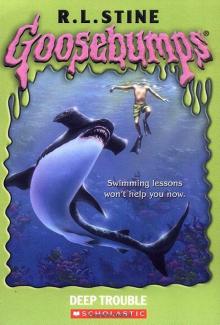

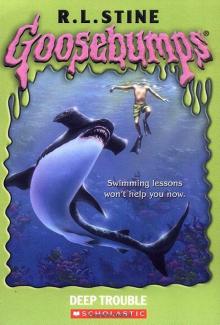

Beware! Deep Trouble (9780545405768)

Deep Trouble (9780545405768) 13 - Piano Lessons Can Be Murder

13 - Piano Lessons Can Be Murder 54 - Don't Go To Sleep

54 - Don't Go To Sleep 29 - Monster Blood III

29 - Monster Blood III![[Goosebumps 29] - Monster Blood III Read online](//i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/13/[goosebumps_29]_-_monster_blood_iii_preview.jpg) [Goosebumps 29] - Monster Blood III

[Goosebumps 29] - Monster Blood III Return of the Mummy

Return of the Mummy![[Goosebumps 31] - Night of the Living Dummy II Read online](//i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/13/[goosebumps_31]_-_night_of_the_living_dummy_ii_preview.jpg) [Goosebumps 31] - Night of the Living Dummy II

[Goosebumps 31] - Night of the Living Dummy II You May Now Kill the Bride

You May Now Kill the Bride 28 - The Cuckoo Clock of Doom

28 - The Cuckoo Clock of Doom 16 - One Day At Horrorland

16 - One Day At Horrorland 47 - Legend of the Lost Legend

47 - Legend of the Lost Legend Phantom of the Auditorium

Phantom of the Auditorium 15 - You Can't Scare Me!

15 - You Can't Scare Me!![[Goosebumps 49] - Vampire Breath Read online](//i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/20/[goosebumps_49]_-_vampire_breath_preview.jpg) [Goosebumps 49] - Vampire Breath

[Goosebumps 49] - Vampire Breath Three Evil Wishes

Three Evil Wishes Party Poopers

Party Poopers 06 - Let's Get Invisible!

06 - Let's Get Invisible! Camp Nowhere

Camp Nowhere Why I'm Afraid of Bees

Why I'm Afraid of Bees![[Goosebumps 60] - Werewolf Skin Read online](//i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/14/[goosebumps_60]_-_werewolf_skin_preview.jpg) [Goosebumps 60] - Werewolf Skin

[Goosebumps 60] - Werewolf Skin Series 2000- Jekyl & Heidi

Series 2000- Jekyl & Heidi Escape from HorrorLand

Escape from HorrorLand![[Goosebumps 08] - The Girl Who Cried Monster Read online](//i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/17/[goosebumps_08]_-_the_girl_who_cried_monster_preview.jpg) [Goosebumps 08] - The Girl Who Cried Monster

[Goosebumps 08] - The Girl Who Cried Monster 18 - Monster Blood II

18 - Monster Blood II![[Goosebumps 28] - The Cuckoo Clock of Doom Read online](//i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/18/[goosebumps_28]_-_the_cuckoo_clock_of_doom_preview.jpg) [Goosebumps 28] - The Cuckoo Clock of Doom

[Goosebumps 28] - The Cuckoo Clock of Doom A Shocker on Shock Street

A Shocker on Shock Street 06 - Eye of the Fortuneteller

06 - Eye of the Fortuneteller Don't Close Your Eyes!

Don't Close Your Eyes! Three Faces of Me

Three Faces of Me The Abominable Snowman of Pasadena

The Abominable Snowman of Pasadena![[Goosebumps 51] - Beware, the Snowman Read online](//i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/14/[goosebumps_51]_-_beware_the_snowman_preview.jpg) [Goosebumps 51] - Beware, the Snowman

[Goosebumps 51] - Beware, the Snowman The Barking Ghost

The Barking Ghost The Wizard of Ooze

The Wizard of Ooze Nightmare in 3-D

Nightmare in 3-D The Girl Who Cried Monster

The Girl Who Cried Monster The Beast 2

The Beast 2 48 - Attack of the Jack-O'-Lanterns

48 - Attack of the Jack-O'-Lanterns 49 - Vampire Breath

49 - Vampire Breath Creature Teacher: The Final Exam

Creature Teacher: The Final Exam The Sequel

The Sequel The Secret

The Secret Overnight

Overnight 57 - My Best Friend is Invisible

57 - My Best Friend is Invisible Night of the Werecat

Night of the Werecat Please Don't Feed the Vampire!

Please Don't Feed the Vampire! The Teacher from Heck

The Teacher from Heck 33 - The Horror at Camp Jellyjam

33 - The Horror at Camp Jellyjam Camp Fear Ghouls

Camp Fear Ghouls The Five Masks of Dr. Screem

The Five Masks of Dr. Screem 41 - Bad Hare Day

41 - Bad Hare Day Can You Keep a Secret?

Can You Keep a Secret? Silent Night 3

Silent Night 3 23 - Return of the Mummy

23 - Return of the Mummy The Scarecrow Walks at Midnight

The Scarecrow Walks at Midnight Series 2000- Return to Horroland

Series 2000- Return to Horroland 07 - Fright Knight

07 - Fright Knight Fear Hall: The Beginning

Fear Hall: The Beginning Help! We Have Strange Powers!

Help! We Have Strange Powers! Goosebumps Most Wanted #5: Dr. Maniac Will See You Now

Goosebumps Most Wanted #5: Dr. Maniac Will See You Now 11 - The Haunted Mask

11 - The Haunted Mask![[Goosebumps 47] - Legend of the Lost Legend Read online](//i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/15/[goosebumps_47]_-_legend_of_the_lost_legend_preview.jpg) [Goosebumps 47] - Legend of the Lost Legend

[Goosebumps 47] - Legend of the Lost Legend 46 - How to Kill a Monster

46 - How to Kill a Monster Party Games

Party Games A Nightmare on Clown Street

A Nightmare on Clown Street The Horror at Camp Jellyjam

The Horror at Camp Jellyjam Deep Trouble 2

Deep Trouble 2 Moonlight Secrets

Moonlight Secrets![[Goosebumps 50] - Calling All Creeps Read online](//i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/15/[goosebumps_50]_-_calling_all_creeps_preview.jpg) [Goosebumps 50] - Calling All Creeps

[Goosebumps 50] - Calling All Creeps Dumb Clucks

Dumb Clucks Judy and the Beast

Judy and the Beast The Heinie Prize

The Heinie Prize Full Moon Halloween

Full Moon Halloween![[Goosebumps 45] - Ghost Camp Read online](//i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/17/[goosebumps_45]_-_ghost_camp_preview.jpg) [Goosebumps 45] - Ghost Camp

[Goosebumps 45] - Ghost Camp First Evil

First Evil![[Goosebumps 22] - Ghost Beach Read online](//i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/17/[goosebumps_22]_-_ghost_beach_preview.jpg) [Goosebumps 22] - Ghost Beach

[Goosebumps 22] - Ghost Beach Switched

Switched 39 - How I Got My Shrunken Head

39 - How I Got My Shrunken Head Toy Terror: Batteries Included

Toy Terror: Batteries Included 32 - The Barking Ghost

32 - The Barking Ghost The Big Blueberry Barf-Off!

The Big Blueberry Barf-Off! The Third Evil

The Third Evil The Blob That Ate Everyone

The Blob That Ate Everyone Return to the Carnival of Horrors

Return to the Carnival of Horrors College Weekend

College Weekend How I Met My Monster (9780545510172)

How I Met My Monster (9780545510172) Heads, You Lose!

Heads, You Lose! Let's Get This Party Haunted!

Let's Get This Party Haunted! Attack of the Mutant

Attack of the Mutant Dance of Death

Dance of Death My Friends Call Me Monster

My Friends Call Me Monster![[Goosebumps 13] - Piano Lessons Can Be Murder Read online](//i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/15/[goosebumps_13]_-_piano_lessons_can_be_murder_preview.jpg) [Goosebumps 13] - Piano Lessons Can Be Murder

[Goosebumps 13] - Piano Lessons Can Be Murder Who Killed the Homecoming Queen?

Who Killed the Homecoming Queen? 58 - Deep Trouble II

58 - Deep Trouble II Body Switchers from Outer Space

Body Switchers from Outer Space![[Goosebumps 09] - Welcome to Camp Nightmare Read online](//i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/18/[goosebumps_09]_-_welcome_to_camp_nightmare_preview.jpg) [Goosebumps 09] - Welcome to Camp Nightmare

[Goosebumps 09] - Welcome to Camp Nightmare The Haunted Car

The Haunted Car The Twisted Tale of Tiki Island

The Twisted Tale of Tiki Island The Great Smelling Bee

The Great Smelling Bee Secret Admirer

Secret Admirer Creep from the Deep

Creep from the Deep![[Goosebumps 25] - Attack of the Mutant Read online](//i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/18/[goosebumps_25]_-_attack_of_the_mutant_preview.jpg) [Goosebumps 25] - Attack of the Mutant

[Goosebumps 25] - Attack of the Mutant Field of Screams

Field of Screams The Creature from Club Lagoona

The Creature from Club Lagoona![[Goosebumps 40] - Night of the Living Dummy III Read online](//i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/16/[goosebumps_40]_-_night_of_the_living_dummy_iii_preview.jpg) [Goosebumps 40] - Night of the Living Dummy III

[Goosebumps 40] - Night of the Living Dummy III 10 - The Ghost Next Door

10 - The Ghost Next Door![[Goosebumps 44] - Say Cheese and Die—Again! Read online](//i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/18/[goosebumps_44]_-_say_cheese_and_die-again_preview.jpg) [Goosebumps 44] - Say Cheese and Die—Again!

[Goosebumps 44] - Say Cheese and Die—Again! Here Comes the Shaggedy

Here Comes the Shaggedy![[Goosebumps 52] - How I Learned to Fly Read online](//i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/16/[goosebumps_52]_-_how_i_learned_to_fly_preview.jpg) [Goosebumps 52] - How I Learned to Fly

[Goosebumps 52] - How I Learned to Fly![[Goosebumps 16] - One Day at HorrorLand Read online](//i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/18/[goosebumps_16]_-_one_day_at_horrorland_preview.jpg) [Goosebumps 16] - One Day at HorrorLand

[Goosebumps 16] - One Day at HorrorLand Trapped in the Circus of Fear

Trapped in the Circus of Fear Series 2000- Are You Terrified Yet?

Series 2000- Are You Terrified Yet? 59 - The Haunted School

59 - The Haunted School![[Goosebumps 24] - Phantom of the Auditorium Read online](//i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/16/[goosebumps_24]_-_phantom_of_the_auditorium_preview.jpg) [Goosebumps 24] - Phantom of the Auditorium

[Goosebumps 24] - Phantom of the Auditorium Series 2000- Horrors of the Black Ring

Series 2000- Horrors of the Black Ring![[Goosebumps 56] - The Curse of Camp Cold Lake Read online](//i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/21/[goosebumps_56]_-_the_curse_of_camp_cold_lake_preview.jpg) [Goosebumps 56] - The Curse of Camp Cold Lake

[Goosebumps 56] - The Curse of Camp Cold Lake All-Night Party

All-Night Party Thrills and Chills

Thrills and Chills Zombie Halloween

Zombie Halloween 04 - Say Cheese and Die!

04 - Say Cheese and Die! The Second Evil

The Second Evil Night of the Creepy Things

Night of the Creepy Things Weirdo Halloween

Weirdo Halloween The Cabinet of Souls

The Cabinet of Souls 44 - Say Cheese and Die—Again

44 - Say Cheese and Die—Again Liar Liar

Liar Liar![[Goosebumps 43] - The Beast from the East Read online](//i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/16/[goosebumps_43]_-_the_beast_from_the_east_preview.jpg) [Goosebumps 43] - The Beast from the East

[Goosebumps 43] - The Beast from the East![[Goosebumps 18] - Monster Blood II Read online](//i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/18/[goosebumps_18]_-_monster_blood_ii_preview.jpg) [Goosebumps 18] - Monster Blood II

[Goosebumps 18] - Monster Blood II The Wrong Number

The Wrong Number They Call Me Creature

They Call Me Creature Spell of the Screaming Jokers

Spell of the Screaming Jokers![[Goosebumps 30] - It Came from Beneath the Sink! Read online](//i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/18/[goosebumps_30]_-_it_came_from_beneath_the_sink_preview.jpg) [Goosebumps 30] - It Came from Beneath the Sink!

[Goosebumps 30] - It Came from Beneath the Sink! Got Cake?

Got Cake? Cheerleaders: The New Evil

Cheerleaders: The New Evil Egg Monsters from Mars

Egg Monsters from Mars Night of the Living Dummy

Night of the Living Dummy Silent Night

Silent Night The Conclusion

The Conclusion 26 - My Hairiest Adventure

26 - My Hairiest Adventure Eye Candy

Eye Candy Welcome to Camp Slither

Welcome to Camp Slither The Howler

The Howler Lizard of Oz

Lizard of Oz Under the Magician's Spell

Under the Magician's Spell![[Goosebumps 02] - Stay Out of the Basement Read online](//i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/19/[goosebumps_02]_-_stay_out_of_the_basement_preview.jpg) [Goosebumps 02] - Stay Out of the Basement

[Goosebumps 02] - Stay Out of the Basement The Knight in Screaming Armor

The Knight in Screaming Armor 05 - The Curse of the Mummy's Tomb

05 - The Curse of the Mummy's Tomb![[Ghosts of Fear Street 06] - Eye of the Fortuneteller Read online](//i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/22/[ghosts_of_fear_street_06]_-_eye_of_the_fortuneteller_preview.jpg) [Ghosts of Fear Street 06] - Eye of the Fortuneteller

[Ghosts of Fear Street 06] - Eye of the Fortuneteller The Beast

The Beast The Best Friend

The Best Friend The Third Horror

The Third Horror Punk'd and Skunked

Punk'd and Skunked![[Goosebumps 19] - Deep Trouble Read online](//i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/16/[goosebumps_19]_-_deep_trouble_preview.jpg) [Goosebumps 19] - Deep Trouble

[Goosebumps 19] - Deep Trouble A Midsummer Night's Scream

A Midsummer Night's Scream Secret Agent Grandma

Secret Agent Grandma![[Goosebumps 55] - The Blob That Ate Everyone Read online](//i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/16/[goosebumps_55]_-_the_blob_that_ate_everyone_preview.jpg) [Goosebumps 55] - The Blob That Ate Everyone

[Goosebumps 55] - The Blob That Ate Everyone Why I'm Not Afraid of Ghosts

Why I'm Not Afraid of Ghosts 34 - Revenge of the Lawn Gnomes

34 - Revenge of the Lawn Gnomes Series 2000- Brain Juice

Series 2000- Brain Juice![[Goosebumps 05] - The Curse of the Mummy's Tomb Read online](//i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/19/[goosebumps_05]_-_the_curse_of_the_mummys_tomb_preview.jpg) [Goosebumps 05] - The Curse of the Mummy's Tomb

[Goosebumps 05] - The Curse of the Mummy's Tomb My Best Friend Is Invisible

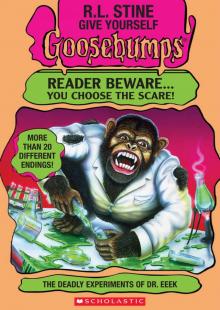

My Best Friend Is Invisible The Deadly Experiments of Dr. Eeek

The Deadly Experiments of Dr. Eeek 19 - Deep Trouble

19 - Deep Trouble Bad Moonlight

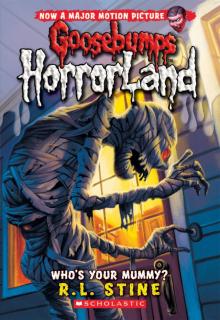

Bad Moonlight Who's Your Mummy?

Who's Your Mummy? Broken Hearts

Broken Hearts The First Horror

The First Horror Series 2000- The Miummy Walks

Series 2000- The Miummy Walks Revenge of the Living Dummy

Revenge of the Living Dummy A Night in Terror Tower

A Night in Terror Tower 12 - Be Careful What You Wish For...

12 - Be Careful What You Wish For...![[Goosebumps 53] - Chicken Chicken Read online](//i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/22/[goosebumps_53]_-_chicken_chicken_preview.jpg) [Goosebumps 53] - Chicken Chicken

[Goosebumps 53] - Chicken Chicken The Wrong Girl

The Wrong Girl Go Eat Worms!

Go Eat Worms! When the Ghost Dog Howls

When the Ghost Dog Howls Escape From Shudder Mansion

Escape From Shudder Mansion The Sitter

The Sitter The Betrayal

The Betrayal The Ooze

The Ooze![[Goosebumps 20] - The Scarecrow Walks at Midnight Read online](//i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/23/[goosebumps_20]_-_the_scarecrow_walks_at_midnight_preview.jpg) [Goosebumps 20] - The Scarecrow Walks at Midnight

[Goosebumps 20] - The Scarecrow Walks at Midnight The Stepsister

The Stepsister Wrong Number 2

Wrong Number 2![[Goosebumps 01] - Welcome to Dead House Read online](//i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/17/[goosebumps_01]_-_welcome_to_dead_house_preview.jpg) [Goosebumps 01] - Welcome to Dead House

[Goosebumps 01] - Welcome to Dead House How I Got My Shrunken Head

How I Got My Shrunken Head Little Camp of Horrors

Little Camp of Horrors![[Goosebumps 62] - Monster Blood IV Read online](//i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/17/[goosebumps_62]_-_monster_blood_iv_preview.jpg) [Goosebumps 62] - Monster Blood IV

[Goosebumps 62] - Monster Blood IV How to Be a Vampire

How to Be a Vampire Attack of the Jack

Attack of the Jack 09 - Welcome to Camp Nightmare

09 - Welcome to Camp Nightmare 40 - Night of the Living Dummy III

40 - Night of the Living Dummy III Daughters of Silence

Daughters of Silence No Survivors

No Survivors![[Goosebumps 34] - Revenge of the Lawn Gnomes Read online](//i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/23/[goosebumps_34]_-_revenge_of_the_lawn_gnomes_preview.jpg) [Goosebumps 34] - Revenge of the Lawn Gnomes

[Goosebumps 34] - Revenge of the Lawn Gnomes Shake, Rattle, and Hurl!

Shake, Rattle, and Hurl! 27 - A Night in Terror Tower

27 - A Night in Terror Tower Fear: 13 Stories of Suspense and Horror

Fear: 13 Stories of Suspense and Horror 36 - The Haunted Mask II

36 - The Haunted Mask II![[Ghosts of Fear Street 07] - Fright Knight Read online](//i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/24/[ghosts_of_fear_street_07]_-_fright_knight_preview.jpg) [Ghosts of Fear Street 07] - Fright Knight

[Ghosts of Fear Street 07] - Fright Knight 07 - Night of the Living Dummy

07 - Night of the Living Dummy The Haunting Hour

The Haunting Hour The Curse of the Creeping Coffin

The Curse of the Creeping Coffin A Sad Mistake

A Sad Mistake Night of the Living Dummy 2

Night of the Living Dummy 2 Welcome to the Wicked Wax Museum

Welcome to the Wicked Wax Museum Midnight Games

Midnight Games The Burning

The Burning The Ghost Next Door

The Ghost Next Door![[Goosebumps 36] - The Haunted Mask II Read online](//i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/24/[goosebumps_36]_-_the_haunted_mask_ii_preview.jpg) [Goosebumps 36] - The Haunted Mask II

[Goosebumps 36] - The Haunted Mask II The Face

The Face 31 - Night of the Living Dummy II

31 - Night of the Living Dummy II![[Goosebumps 42] - Egg Monsters From Mars Read online](//i1.bookreadfree.com/i1/03/27/[goosebumps_42]_-_egg_monsters_from_mars_preview.jpg) [Goosebumps 42] - Egg Monsters From Mars

[Goosebumps 42] - Egg Monsters From Mars Trick or Trap

Trick or Trap The Headless Ghost

The Headless Ghost Beware of the Purple Peanut Butter

Beware of the Purple Peanut Butter The Ghost of Slappy

The Ghost of Slappy Don't Go to Sleep

Don't Go to Sleep![[Goosebumps 38] - The Abominable Snowman of Pasadena Read online](//i1.bookreadfree.com/i1/03/27/[goosebumps_38]_-_the_abominable_snowman_of_pasadena_preview.jpg) [Goosebumps 38] - The Abominable Snowman of Pasadena

[Goosebumps 38] - The Abominable Snowman of Pasadena 43 - The Beast from the East

43 - The Beast from the East 51 - Beware, the Snowman

51 - Beware, the Snowman![[Goosebumps 33] - The Horror at Camp Jellyjam Read online](//i1.bookreadfree.com/i1/03/29/[goosebumps_33]_-_the_horror_at_camp_jellyjam_preview.jpg) [Goosebumps 33] - The Horror at Camp Jellyjam

[Goosebumps 33] - The Horror at Camp Jellyjam The New Year's Party

The New Year's Party![[Goosebumps 32] - The Barking Ghost Read online](//i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/25/[goosebumps_32]_-_the_barking_ghost_preview.jpg) [Goosebumps 32] - The Barking Ghost

[Goosebumps 32] - The Barking Ghost Cuckoo Clock of Doom

Cuckoo Clock of Doom High Tide (9781481413824)

High Tide (9781481413824) Zombie Town

Zombie Town![[Goosebumps 21] - Go Eat Worms! Read online](//i1.bookreadfree.com/i1/03/27/[goosebumps_21]_-_go_eat_worms_preview.jpg) [Goosebumps 21] - Go Eat Worms!

[Goosebumps 21] - Go Eat Worms! Forbidden Secrets

Forbidden Secrets Night of the Giant Everything

Night of the Giant Everything![[Goosebumps 07] - Night of the Living Dummy Read online](//i1.bookreadfree.com/i1/03/28/[goosebumps_07]_-_night_of_the_living_dummy_preview.jpg) [Goosebumps 07] - Night of the Living Dummy

[Goosebumps 07] - Night of the Living Dummy Give Me a K-I-L-L

Give Me a K-I-L-L Ghouls Gone Wild

Ghouls Gone Wild Night In Werewolf Woods

Night In Werewolf Woods The Confession

The Confession The Good, the Bad and the Very Slimy

The Good, the Bad and the Very Slimy It Came From Beneath The Sink

It Came From Beneath The Sink Legend of the Lost Legend

Legend of the Lost Legend First Date

First Date The Dead Boyfriend

The Dead Boyfriend![[Goosebumps 59] - The Haunted School Read online](//i1.bookreadfree.com/i1/03/28/[goosebumps_59]_-_the_haunted_school_preview.jpg) [Goosebumps 59] - The Haunted School

[Goosebumps 59] - The Haunted School![[Goosebumps 11] - The Haunted Mask Read online](//i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/26/[goosebumps_11]_-_the_haunted_mask_preview.jpg) [Goosebumps 11] - The Haunted Mask

[Goosebumps 11] - The Haunted Mask Halloween Party

Halloween Party Locker 13

Locker 13 Streets of Panic Park

Streets of Panic Park Dudes, the School Is Haunted!

Dudes, the School Is Haunted! 01 - Welcome to Dead House

01 - Welcome to Dead House A New Fear

A New Fear It's Alive! It's Alive!

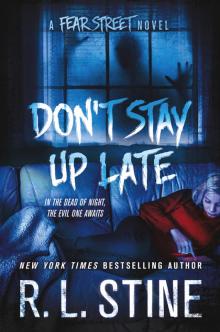

It's Alive! It's Alive! Don't Stay Up Late

Don't Stay Up Late Stay Out of the Basement

Stay Out of the Basement The Cheater

The Cheater The Awakening Evil

The Awakening Evil Attack of the Jack-O'-Lanterns

Attack of the Jack-O'-Lanterns What Scares You the Most?

What Scares You the Most? 22 - Ghost Beach

22 - Ghost Beach Slappy Birthday to You

Slappy Birthday to You 55 - The Blob That Ate Everyone

55 - The Blob That Ate Everyone 45 - Ghost Camp

45 - Ghost Camp Ghost Beach

Ghost Beach Scream of the Evil Genie

Scream of the Evil Genie Silent Night 2

Silent Night 2 Escape from the Carnival of Horrors

Escape from the Carnival of Horrors 60 - Werewolf Skin

60 - Werewolf Skin Welcome to Camp Nightmare

Welcome to Camp Nightmare The Beast from the East

The Beast from the East![[Goosebumps 61] - I Live in Your Basement Read online](//i1.bookreadfree.com/i1/04/01/[goosebumps_61]_-_i_live_in_your_basement_preview.jpg) [Goosebumps 61] - I Live in Your Basement

[Goosebumps 61] - I Live in Your Basement The 12 Screams of Christmas

The 12 Screams of Christmas The Lost Girl

The Lost Girl Dear Diary, I'm Dead

Dear Diary, I'm Dead Don't Forget Me!

Don't Forget Me! 53 - Chicken Chicken

53 - Chicken Chicken Nightmare Hour

Nightmare Hour Deep in the Jungle of Doom

Deep in the Jungle of Doom Eye Of The Fortuneteller

Eye Of The Fortuneteller![[Goosebumps 14] - The Werewolf of Fever Swamp Read online](//i1.bookreadfree.com/i1/04/04/[goosebumps_14]_-_the_werewolf_of_fever_swamp_preview.jpg) [Goosebumps 14] - The Werewolf of Fever Swamp

[Goosebumps 14] - The Werewolf of Fever Swamp![[Goosebumps 46] - How to Kill a Monster Read online](//i1.bookreadfree.com/i1/04/03/[goosebumps_46]_-_how_to_kill_a_monster_preview.jpg) [Goosebumps 46] - How to Kill a Monster

[Goosebumps 46] - How to Kill a Monster Attack of the Beastly Babysitter

Attack of the Beastly Babysitter![[Goosebumps 35] - A Shocker on Shock Street Read online](//i1.bookreadfree.com/i1/04/04/[goosebumps_35]_-_a_shocker_on_shock_street_preview.jpg) [Goosebumps 35] - A Shocker on Shock Street

[Goosebumps 35] - A Shocker on Shock Street![[Goosebumps 23] - Return of the Mummy Read online](//i1.bookreadfree.com/i1/04/04/[goosebumps_23]_-_return_of_the_mummy_preview.jpg) [Goosebumps 23] - Return of the Mummy

[Goosebumps 23] - Return of the Mummy The Children of Fear

The Children of Fear The Dare

The Dare Say Cheese - And Die Screaming!

Say Cheese - And Die Screaming! 56- The Curse of Camp Cold Lake

56- The Curse of Camp Cold Lake Little Shop of Hamsters

Little Shop of Hamsters Monster Blood IV g-62

Monster Blood IV g-62 Monster Blood

Monster Blood Slappy New Year!

Slappy New Year! 24 - Phantom of the Auditorium

24 - Phantom of the Auditorium 42 - Egg Monsters from Mars

42 - Egg Monsters from Mars 52 - How I Learned to Fly

52 - How I Learned to Fly Temptation

Temptation Party Summer

Party Summer The Scream of the Haunted Mask

The Scream of the Haunted Mask![[Goosebumps 06] - Let's Get Invisible Read online](//i1.bookreadfree.com/i1/04/05/[goosebumps_06]_-_lets_get_invisible_preview.jpg) [Goosebumps 06] - Let's Get Invisible

[Goosebumps 06] - Let's Get Invisible![[Goosebumps 10] - The Ghost Next Door Read online](//i1.bookreadfree.com/i1/04/05/[goosebumps_10]_-_the_ghost_next_door_preview.jpg) [Goosebumps 10] - The Ghost Next Door

[Goosebumps 10] - The Ghost Next Door Goosebumps Most Wanted - 02 - Son of Slappy

Goosebumps Most Wanted - 02 - Son of Slappy Calling All Birdbrains

Calling All Birdbrains Series 2000- Headless Halloween

Series 2000- Headless Halloween Dr. Maniac vs. Robby Schwartz

Dr. Maniac vs. Robby Schwartz Who Let the Ghosts Out?

Who Let the Ghosts Out? Battle of the Dum Diddys

Battle of the Dum Diddys 38 - The Abominable Snowman of Pasadena

38 - The Abominable Snowman of Pasadena 08 - The Girl Who Cried Monster

08 - The Girl Who Cried Monster Don't Scream!

Don't Scream! Visitors

Visitors Werewolf of Fever Swamp

Werewolf of Fever Swamp![[Goosebumps 54] - Don't Go To Sleep Read online](//i1.bookreadfree.com/i2/04/06/[goosebumps_54]_-_dont_go_to_sleep_preview.jpg) [Goosebumps 54] - Don't Go To Sleep

[Goosebumps 54] - Don't Go To Sleep![[Goosebumps 58] - Deep Trouble II Read online](//i1.bookreadfree.com/i2/04/08/[goosebumps_58]_-_deep_trouble_ii_preview.jpg) [Goosebumps 58] - Deep Trouble II

[Goosebumps 58] - Deep Trouble II Werewolf Skin g-60

Werewolf Skin g-60 37 - The Headless Ghost

37 - The Headless Ghost Trapped in Bat Wing Hall

Trapped in Bat Wing Hall Fright Christmas

Fright Christmas Bad Dreams

Bad Dreams Revenge of the Lawn Gnomes

Revenge of the Lawn Gnomes![[Goosebumps 04] - Say Cheese and Die! Read online](//i1.bookreadfree.com/i2/04/07/[goosebumps_04]_-_say_cheese_and_die_preview.jpg) [Goosebumps 04] - Say Cheese and Die!

[Goosebumps 04] - Say Cheese and Die!![[Goosebumps 17] - Why I'm Afraid of Bees Read online](//i1.bookreadfree.com/i2/04/07/[goosebumps_17]_-_why_im_afraid_of_bees_preview.jpg) [Goosebumps 17] - Why I'm Afraid of Bees

[Goosebumps 17] - Why I'm Afraid of Bees The Curse of Camp Cold Lake g-56

The Curse of Camp Cold Lake g-56 Say Cheese and Die--Again!

Say Cheese and Die--Again! Fifth-Grade Zombies

Fifth-Grade Zombies Revenge of the Invisible Boy

Revenge of the Invisible Boy The Dummy Meets the Mummy!

The Dummy Meets the Mummy! Beware, the Snowman

Beware, the Snowman Welcome to Smellville

Welcome to Smellville Camp Daze

Camp Daze Calling All Creeps

Calling All Creeps Missing

Missing How I Learned to Fly

How I Learned to Fly I Live In Your Basement

I Live In Your Basement Ghost Camp

Ghost Camp Chicken Chicken

Chicken Chicken My Friend Slappy

My Friend Slappy The New Girl

The New Girl Diary of a Dummy

Diary of a Dummy Monster Blood is Back

Monster Blood is Back Beware, The Snowman (Goosebumps #51)

Beware, The Snowman (Goosebumps #51) Give Yourself Goosebumps: Beware of the Purple Peanut Butter

Give Yourself Goosebumps: Beware of the Purple Peanut Butter Drop Dead Gorgeous

Drop Dead Gorgeous Claws!

Claws! 61 - I Live in Your Basement

61 - I Live in Your Basement Shadow Girl

Shadow Girl 14 - The Werewolf of Fever Swamp

14 - The Werewolf of Fever Swamp You Can't Scare Me!

You Can't Scare Me! The Sign of Fear

The Sign of Fear Red Rain

Red Rain The Horror at Chiller House

The Horror at Chiller House Welcome to Dead House

Welcome to Dead House What Holly Heard

What Holly Heard Have You Met My Ghoulfriend?

Have You Met My Ghoulfriend? It Came From Ohio!

It Came From Ohio! The Barking Ghost g-32

The Barking Ghost g-32 20 - The Scarecrow Walks at Midnight

20 - The Scarecrow Walks at Midnight 25 - Attack of the Mutant

25 - Attack of the Mutant Vampire Breath

Vampire Breath Please Do Not Feed the Weirdo

Please Do Not Feed the Weirdo![[Goosebumps 12] - Be Careful What You Wish For... Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/12/[goosebumps_12]_-_be_careful_what_you_wish_for__preview.jpg) [Goosebumps 12] - Be Careful What You Wish For...

[Goosebumps 12] - Be Careful What You Wish For... Fear Games

Fear Games Red Rain: A Novel

Red Rain: A Novel Night of the Living Dummy 3

Night of the Living Dummy 3 Werewolf Skin

Werewolf Skin Curse of the Mummy's Tomb

Curse of the Mummy's Tomb![[Goosebumps 37] - The Headless Ghost Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/17/[goosebumps_37]_-_the_headless_ghost_preview.jpg) [Goosebumps 37] - The Headless Ghost

[Goosebumps 37] - The Headless Ghost Escape from Camp Run-For-Your-Life

Escape from Camp Run-For-Your-Life Diary of a Mad Mummy

Diary of a Mad Mummy Little Comic Shop of Horrors

Little Comic Shop of Horrors My Name Is Evil

My Name Is Evil The Rottenest Angel

The Rottenest Angel Monster Blood For Breakfast!

Monster Blood For Breakfast!![[Goosebumps 41] - Bad Hare Day Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/16/[goosebumps_41]_-_bad_hare_day_preview.jpg) [Goosebumps 41] - Bad Hare Day

[Goosebumps 41] - Bad Hare Day The Adventures of Shrinkman

The Adventures of Shrinkman House of Whispers

House of Whispers The Taste of Night

The Taste of Night Say Cheese and Die!

Say Cheese and Die! Wanted

Wanted One Day at Horrorland

One Day at Horrorland Scream and Scream Again!

Scream and Scream Again! Haunted Mask II

Haunted Mask II![[Goosebumps 03] - Monster Blood Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/16/[goosebumps_03]_-_monster_blood_preview.jpg) [Goosebumps 03] - Monster Blood

[Goosebumps 03] - Monster Blood Tick Tock, You're Dead!

Tick Tock, You're Dead! Lose, Team, Lose!

Lose, Team, Lose! Night of the Puppet People

Night of the Puppet People The Boy Who Ate Fear Street

The Boy Who Ate Fear Street The Birthday Party of No Return!

The Birthday Party of No Return! Toy Terror

Toy Terror![[Goosebumps 27] - A Night in Terror Tower Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/16/[goosebumps_27]_-_a_night_in_terror_tower_preview.jpg) [Goosebumps 27] - A Night in Terror Tower

[Goosebumps 27] - A Night in Terror Tower![[Goosebumps 39] - How I Got My Shrunken Head Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/16/[goosebumps_39]_-_how_i_got_my_shrunken_head_preview.jpg) [Goosebumps 39] - How I Got My Shrunken Head

[Goosebumps 39] - How I Got My Shrunken Head 17 - Why I'm Afraid of Bees

17 - Why I'm Afraid of Bees![[Goosebumps 57] - My Best Friend is Invisible Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/16/[goosebumps_57]_-_my_best_friend_is_invisible_preview.jpg) [Goosebumps 57] - My Best Friend is Invisible

[Goosebumps 57] - My Best Friend is Invisible They Call Me the Night Howler!

They Call Me the Night Howler! House of a Thousand Screams

House of a Thousand Screams The Curse of Camp Cold Lake

The Curse of Camp Cold Lake Mostly Ghostly Freaks and Shrieks

Mostly Ghostly Freaks and Shrieks Dangerous Girls

Dangerous Girls 30 - It Came from Beneath the Sink

30 - It Came from Beneath the Sink Killer's Kiss

Killer's Kiss Attack of the Graveyard Ghouls

Attack of the Graveyard Ghouls 62 - Monster Blood IV

62 - Monster Blood IV Double Date

Double Date The Secret Bedroom

The Secret Bedroom![[Goosebumps 48] - Attack of the Jack-O'-Lanterns Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/17/[goosebumps_48]_-_attack_of_the_jack-o-lanterns_preview.jpg) [Goosebumps 48] - Attack of the Jack-O'-Lanterns

[Goosebumps 48] - Attack of the Jack-O'-Lanterns![[Goosebumps 26] - My Hairiest Adventure Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/17/[goosebumps_26]_-_my_hairiest_adventure_preview.jpg) [Goosebumps 26] - My Hairiest Adventure

[Goosebumps 26] - My Hairiest Adventure 50 - Calling All Creeps!

50 - Calling All Creeps! The Hidden Evil

The Hidden Evil I Am Slappy's Evil Twin

I Am Slappy's Evil Twin Planet of the Lawn Gnomes

Planet of the Lawn Gnomes Piano Lessons Can Be Murder

Piano Lessons Can Be Murder Let's Get Invisible!

Let's Get Invisible! Why I Quit Zombie School

Why I Quit Zombie School Bride of the Living Dummy

Bride of the Living Dummy 03 - Monster Blood

03 - Monster Blood The Attack of the Aqua Apes

The Attack of the Aqua Apes![[Goosebumps 15] - You Can't Scare Me! Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/13/[goosebumps_15]_-_you_cant_scare_me_preview.jpg) [Goosebumps 15] - You Can't Scare Me!

[Goosebumps 15] - You Can't Scare Me! Goosebumps the Movie

Goosebumps the Movie The New Girl (Fear Street)

The New Girl (Fear Street) 21 - Go Eat Worms!

21 - Go Eat Worms! 02 - Stay Out of the Basement

02 - Stay Out of the Basement The Second Horror

The Second Horror Scare School

Scare School Beware!

Beware! Deep Trouble (9780545405768)

Deep Trouble (9780545405768) 13 - Piano Lessons Can Be Murder

13 - Piano Lessons Can Be Murder 54 - Don't Go To Sleep

54 - Don't Go To Sleep 29 - Monster Blood III

29 - Monster Blood III![[Goosebumps 29] - Monster Blood III Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/13/[goosebumps_29]_-_monster_blood_iii_preview.jpg) [Goosebumps 29] - Monster Blood III

[Goosebumps 29] - Monster Blood III Return of the Mummy

Return of the Mummy![[Goosebumps 31] - Night of the Living Dummy II Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/13/[goosebumps_31]_-_night_of_the_living_dummy_ii_preview.jpg) [Goosebumps 31] - Night of the Living Dummy II

[Goosebumps 31] - Night of the Living Dummy II You May Now Kill the Bride

You May Now Kill the Bride 28 - The Cuckoo Clock of Doom

28 - The Cuckoo Clock of Doom 16 - One Day At Horrorland

16 - One Day At Horrorland 47 - Legend of the Lost Legend

47 - Legend of the Lost Legend Phantom of the Auditorium

Phantom of the Auditorium 15 - You Can't Scare Me!

15 - You Can't Scare Me!![[Goosebumps 49] - Vampire Breath Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/20/[goosebumps_49]_-_vampire_breath_preview.jpg) [Goosebumps 49] - Vampire Breath

[Goosebumps 49] - Vampire Breath Three Evil Wishes

Three Evil Wishes Party Poopers

Party Poopers 06 - Let's Get Invisible!

06 - Let's Get Invisible! Camp Nowhere

Camp Nowhere Why I'm Afraid of Bees

Why I'm Afraid of Bees![[Goosebumps 60] - Werewolf Skin Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/14/[goosebumps_60]_-_werewolf_skin_preview.jpg) [Goosebumps 60] - Werewolf Skin

[Goosebumps 60] - Werewolf Skin Series 2000- Jekyl & Heidi

Series 2000- Jekyl & Heidi Escape from HorrorLand

Escape from HorrorLand![[Goosebumps 08] - The Girl Who Cried Monster Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/17/[goosebumps_08]_-_the_girl_who_cried_monster_preview.jpg) [Goosebumps 08] - The Girl Who Cried Monster

[Goosebumps 08] - The Girl Who Cried Monster 18 - Monster Blood II

18 - Monster Blood II![[Goosebumps 28] - The Cuckoo Clock of Doom Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/18/[goosebumps_28]_-_the_cuckoo_clock_of_doom_preview.jpg) [Goosebumps 28] - The Cuckoo Clock of Doom

[Goosebumps 28] - The Cuckoo Clock of Doom A Shocker on Shock Street

A Shocker on Shock Street 06 - Eye of the Fortuneteller

06 - Eye of the Fortuneteller Don't Close Your Eyes!

Don't Close Your Eyes! Three Faces of Me

Three Faces of Me The Abominable Snowman of Pasadena

The Abominable Snowman of Pasadena![[Goosebumps 51] - Beware, the Snowman Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/14/[goosebumps_51]_-_beware_the_snowman_preview.jpg) [Goosebumps 51] - Beware, the Snowman

[Goosebumps 51] - Beware, the Snowman The Barking Ghost

The Barking Ghost The Wizard of Ooze

The Wizard of Ooze Nightmare in 3-D

Nightmare in 3-D The Girl Who Cried Monster

The Girl Who Cried Monster The Beast 2

The Beast 2 48 - Attack of the Jack-O'-Lanterns

48 - Attack of the Jack-O'-Lanterns 49 - Vampire Breath

49 - Vampire Breath Creature Teacher: The Final Exam

Creature Teacher: The Final Exam The Sequel

The Sequel The Secret

The Secret Overnight

Overnight 57 - My Best Friend is Invisible

57 - My Best Friend is Invisible Night of the Werecat

Night of the Werecat Please Don't Feed the Vampire!

Please Don't Feed the Vampire! The Teacher from Heck

The Teacher from Heck 33 - The Horror at Camp Jellyjam

33 - The Horror at Camp Jellyjam Camp Fear Ghouls

Camp Fear Ghouls The Five Masks of Dr. Screem

The Five Masks of Dr. Screem 41 - Bad Hare Day

41 - Bad Hare Day Can You Keep a Secret?

Can You Keep a Secret? Silent Night 3

Silent Night 3 23 - Return of the Mummy

23 - Return of the Mummy The Scarecrow Walks at Midnight

The Scarecrow Walks at Midnight Series 2000- Return to Horroland

Series 2000- Return to Horroland 07 - Fright Knight

07 - Fright Knight Fear Hall: The Beginning

Fear Hall: The Beginning Help! We Have Strange Powers!

Help! We Have Strange Powers! Goosebumps Most Wanted #5: Dr. Maniac Will See You Now

Goosebumps Most Wanted #5: Dr. Maniac Will See You Now 11 - The Haunted Mask

11 - The Haunted Mask![[Goosebumps 47] - Legend of the Lost Legend Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/15/[goosebumps_47]_-_legend_of_the_lost_legend_preview.jpg) [Goosebumps 47] - Legend of the Lost Legend

[Goosebumps 47] - Legend of the Lost Legend 46 - How to Kill a Monster

46 - How to Kill a Monster Party Games

Party Games A Nightmare on Clown Street

A Nightmare on Clown Street The Horror at Camp Jellyjam

The Horror at Camp Jellyjam Deep Trouble 2

Deep Trouble 2 Moonlight Secrets

Moonlight Secrets![[Goosebumps 50] - Calling All Creeps Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/15/[goosebumps_50]_-_calling_all_creeps_preview.jpg) [Goosebumps 50] - Calling All Creeps

[Goosebumps 50] - Calling All Creeps Dumb Clucks

Dumb Clucks Judy and the Beast

Judy and the Beast The Heinie Prize

The Heinie Prize Full Moon Halloween

Full Moon Halloween![[Goosebumps 45] - Ghost Camp Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/17/[goosebumps_45]_-_ghost_camp_preview.jpg) [Goosebumps 45] - Ghost Camp

[Goosebumps 45] - Ghost Camp First Evil

First Evil![[Goosebumps 22] - Ghost Beach Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/17/[goosebumps_22]_-_ghost_beach_preview.jpg) [Goosebumps 22] - Ghost Beach

[Goosebumps 22] - Ghost Beach Switched

Switched 39 - How I Got My Shrunken Head

39 - How I Got My Shrunken Head Toy Terror: Batteries Included

Toy Terror: Batteries Included 32 - The Barking Ghost

32 - The Barking Ghost The Big Blueberry Barf-Off!

The Big Blueberry Barf-Off! The Third Evil

The Third Evil The Blob That Ate Everyone

The Blob That Ate Everyone Return to the Carnival of Horrors

Return to the Carnival of Horrors College Weekend

College Weekend How I Met My Monster (9780545510172)

How I Met My Monster (9780545510172) Heads, You Lose!

Heads, You Lose! Let's Get This Party Haunted!

Let's Get This Party Haunted! Attack of the Mutant

Attack of the Mutant Dance of Death

Dance of Death My Friends Call Me Monster

My Friends Call Me Monster![[Goosebumps 13] - Piano Lessons Can Be Murder Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/15/[goosebumps_13]_-_piano_lessons_can_be_murder_preview.jpg) [Goosebumps 13] - Piano Lessons Can Be Murder

[Goosebumps 13] - Piano Lessons Can Be Murder Who Killed the Homecoming Queen?

Who Killed the Homecoming Queen? 58 - Deep Trouble II

58 - Deep Trouble II Body Switchers from Outer Space

Body Switchers from Outer Space![[Goosebumps 09] - Welcome to Camp Nightmare Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/18/[goosebumps_09]_-_welcome_to_camp_nightmare_preview.jpg) [Goosebumps 09] - Welcome to Camp Nightmare

[Goosebumps 09] - Welcome to Camp Nightmare The Haunted Car

The Haunted Car The Twisted Tale of Tiki Island

The Twisted Tale of Tiki Island The Great Smelling Bee

The Great Smelling Bee Secret Admirer

Secret Admirer Creep from the Deep

Creep from the Deep![[Goosebumps 25] - Attack of the Mutant Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/18/[goosebumps_25]_-_attack_of_the_mutant_preview.jpg) [Goosebumps 25] - Attack of the Mutant

[Goosebumps 25] - Attack of the Mutant Field of Screams

Field of Screams The Creature from Club Lagoona

The Creature from Club Lagoona![[Goosebumps 40] - Night of the Living Dummy III Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/16/[goosebumps_40]_-_night_of_the_living_dummy_iii_preview.jpg) [Goosebumps 40] - Night of the Living Dummy III

[Goosebumps 40] - Night of the Living Dummy III 10 - The Ghost Next Door

10 - The Ghost Next Door![[Goosebumps 44] - Say Cheese and Die—Again! Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/18/[goosebumps_44]_-_say_cheese_and_die-again_preview.jpg) [Goosebumps 44] - Say Cheese and Die—Again!

[Goosebumps 44] - Say Cheese and Die—Again! Here Comes the Shaggedy

Here Comes the Shaggedy![[Goosebumps 52] - How I Learned to Fly Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/16/[goosebumps_52]_-_how_i_learned_to_fly_preview.jpg) [Goosebumps 52] - How I Learned to Fly

[Goosebumps 52] - How I Learned to Fly![[Goosebumps 16] - One Day at HorrorLand Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/18/[goosebumps_16]_-_one_day_at_horrorland_preview.jpg) [Goosebumps 16] - One Day at HorrorLand

[Goosebumps 16] - One Day at HorrorLand Trapped in the Circus of Fear

Trapped in the Circus of Fear Series 2000- Are You Terrified Yet?

Series 2000- Are You Terrified Yet? 59 - The Haunted School

59 - The Haunted School![[Goosebumps 24] - Phantom of the Auditorium Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/16/[goosebumps_24]_-_phantom_of_the_auditorium_preview.jpg) [Goosebumps 24] - Phantom of the Auditorium

[Goosebumps 24] - Phantom of the Auditorium Series 2000- Horrors of the Black Ring

Series 2000- Horrors of the Black Ring![[Goosebumps 56] - The Curse of Camp Cold Lake Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/21/[goosebumps_56]_-_the_curse_of_camp_cold_lake_preview.jpg) [Goosebumps 56] - The Curse of Camp Cold Lake

[Goosebumps 56] - The Curse of Camp Cold Lake All-Night Party

All-Night Party Thrills and Chills

Thrills and Chills Zombie Halloween

Zombie Halloween 04 - Say Cheese and Die!

04 - Say Cheese and Die! The Second Evil

The Second Evil Night of the Creepy Things

Night of the Creepy Things Weirdo Halloween

Weirdo Halloween The Cabinet of Souls

The Cabinet of Souls 44 - Say Cheese and Die—Again

44 - Say Cheese and Die—Again Liar Liar

Liar Liar![[Goosebumps 43] - The Beast from the East Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/16/[goosebumps_43]_-_the_beast_from_the_east_preview.jpg) [Goosebumps 43] - The Beast from the East

[Goosebumps 43] - The Beast from the East![[Goosebumps 18] - Monster Blood II Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/18/[goosebumps_18]_-_monster_blood_ii_preview.jpg) [Goosebumps 18] - Monster Blood II

[Goosebumps 18] - Monster Blood II The Wrong Number

The Wrong Number They Call Me Creature

They Call Me Creature Spell of the Screaming Jokers

Spell of the Screaming Jokers![[Goosebumps 30] - It Came from Beneath the Sink! Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/18/[goosebumps_30]_-_it_came_from_beneath_the_sink_preview.jpg) [Goosebumps 30] - It Came from Beneath the Sink!

[Goosebumps 30] - It Came from Beneath the Sink! Got Cake?

Got Cake? Cheerleaders: The New Evil

Cheerleaders: The New Evil Egg Monsters from Mars

Egg Monsters from Mars Night of the Living Dummy

Night of the Living Dummy Silent Night

Silent Night The Conclusion

The Conclusion 26 - My Hairiest Adventure

26 - My Hairiest Adventure Eye Candy

Eye Candy Welcome to Camp Slither

Welcome to Camp Slither The Howler

The Howler Lizard of Oz

Lizard of Oz Under the Magician's Spell

Under the Magician's Spell![[Goosebumps 02] - Stay Out of the Basement Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/19/[goosebumps_02]_-_stay_out_of_the_basement_preview.jpg) [Goosebumps 02] - Stay Out of the Basement

[Goosebumps 02] - Stay Out of the Basement The Knight in Screaming Armor

The Knight in Screaming Armor 05 - The Curse of the Mummy's Tomb

05 - The Curse of the Mummy's Tomb![[Ghosts of Fear Street 06] - Eye of the Fortuneteller Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/22/[ghosts_of_fear_street_06]_-_eye_of_the_fortuneteller_preview.jpg) [Ghosts of Fear Street 06] - Eye of the Fortuneteller

[Ghosts of Fear Street 06] - Eye of the Fortuneteller The Beast

The Beast The Best Friend

The Best Friend The Third Horror

The Third Horror Punk'd and Skunked

Punk'd and Skunked![[Goosebumps 19] - Deep Trouble Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/16/[goosebumps_19]_-_deep_trouble_preview.jpg) [Goosebumps 19] - Deep Trouble

[Goosebumps 19] - Deep Trouble A Midsummer Night's Scream

A Midsummer Night's Scream Secret Agent Grandma

Secret Agent Grandma![[Goosebumps 55] - The Blob That Ate Everyone Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/16/[goosebumps_55]_-_the_blob_that_ate_everyone_preview.jpg) [Goosebumps 55] - The Blob That Ate Everyone

[Goosebumps 55] - The Blob That Ate Everyone Why I'm Not Afraid of Ghosts

Why I'm Not Afraid of Ghosts 34 - Revenge of the Lawn Gnomes

34 - Revenge of the Lawn Gnomes Series 2000- Brain Juice

Series 2000- Brain Juice![[Goosebumps 05] - The Curse of the Mummy's Tomb Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/19/[goosebumps_05]_-_the_curse_of_the_mummys_tomb_preview.jpg) [Goosebumps 05] - The Curse of the Mummy's Tomb

[Goosebumps 05] - The Curse of the Mummy's Tomb My Best Friend Is Invisible

My Best Friend Is Invisible The Deadly Experiments of Dr. Eeek

The Deadly Experiments of Dr. Eeek 19 - Deep Trouble

19 - Deep Trouble Bad Moonlight

Bad Moonlight Who's Your Mummy?

Who's Your Mummy? Broken Hearts

Broken Hearts The First Horror

The First Horror Series 2000- The Miummy Walks

Series 2000- The Miummy Walks Revenge of the Living Dummy

Revenge of the Living Dummy A Night in Terror Tower

A Night in Terror Tower 12 - Be Careful What You Wish For...

12 - Be Careful What You Wish For...![[Goosebumps 53] - Chicken Chicken Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/22/[goosebumps_53]_-_chicken_chicken_preview.jpg) [Goosebumps 53] - Chicken Chicken

[Goosebumps 53] - Chicken Chicken The Wrong Girl

The Wrong Girl Go Eat Worms!

Go Eat Worms! When the Ghost Dog Howls

When the Ghost Dog Howls Escape From Shudder Mansion

Escape From Shudder Mansion The Sitter

The Sitter The Betrayal

The Betrayal The Ooze

The Ooze![[Goosebumps 20] - The Scarecrow Walks at Midnight Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/23/[goosebumps_20]_-_the_scarecrow_walks_at_midnight_preview.jpg) [Goosebumps 20] - The Scarecrow Walks at Midnight

[Goosebumps 20] - The Scarecrow Walks at Midnight The Stepsister

The Stepsister Wrong Number 2

Wrong Number 2![[Goosebumps 01] - Welcome to Dead House Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/17/[goosebumps_01]_-_welcome_to_dead_house_preview.jpg) [Goosebumps 01] - Welcome to Dead House

[Goosebumps 01] - Welcome to Dead House How I Got My Shrunken Head

How I Got My Shrunken Head Little Camp of Horrors

Little Camp of Horrors![[Goosebumps 62] - Monster Blood IV Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/17/[goosebumps_62]_-_monster_blood_iv_preview.jpg) [Goosebumps 62] - Monster Blood IV

[Goosebumps 62] - Monster Blood IV How to Be a Vampire

How to Be a Vampire Attack of the Jack

Attack of the Jack 09 - Welcome to Camp Nightmare

09 - Welcome to Camp Nightmare 40 - Night of the Living Dummy III

40 - Night of the Living Dummy III Daughters of Silence

Daughters of Silence No Survivors

No Survivors![[Goosebumps 34] - Revenge of the Lawn Gnomes Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/23/[goosebumps_34]_-_revenge_of_the_lawn_gnomes_preview.jpg) [Goosebumps 34] - Revenge of the Lawn Gnomes

[Goosebumps 34] - Revenge of the Lawn Gnomes Shake, Rattle, and Hurl!

Shake, Rattle, and Hurl! 27 - A Night in Terror Tower

27 - A Night in Terror Tower Fear: 13 Stories of Suspense and Horror

Fear: 13 Stories of Suspense and Horror 36 - The Haunted Mask II

36 - The Haunted Mask II![[Ghosts of Fear Street 07] - Fright Knight Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/24/[ghosts_of_fear_street_07]_-_fright_knight_preview.jpg) [Ghosts of Fear Street 07] - Fright Knight

[Ghosts of Fear Street 07] - Fright Knight 07 - Night of the Living Dummy

07 - Night of the Living Dummy The Haunting Hour

The Haunting Hour The Curse of the Creeping Coffin

The Curse of the Creeping Coffin A Sad Mistake

A Sad Mistake Night of the Living Dummy 2

Night of the Living Dummy 2 Welcome to the Wicked Wax Museum

Welcome to the Wicked Wax Museum Midnight Games

Midnight Games The Burning

The Burning The Ghost Next Door

The Ghost Next Door![[Goosebumps 36] - The Haunted Mask II Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/24/[goosebumps_36]_-_the_haunted_mask_ii_preview.jpg) [Goosebumps 36] - The Haunted Mask II

[Goosebumps 36] - The Haunted Mask II The Face

The Face 31 - Night of the Living Dummy II

31 - Night of the Living Dummy II![[Goosebumps 42] - Egg Monsters From Mars Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i1/03/27/[goosebumps_42]_-_egg_monsters_from_mars_preview.jpg) [Goosebumps 42] - Egg Monsters From Mars

[Goosebumps 42] - Egg Monsters From Mars Trick or Trap

Trick or Trap The Headless Ghost

The Headless Ghost Beware of the Purple Peanut Butter

Beware of the Purple Peanut Butter The Ghost of Slappy

The Ghost of Slappy Don't Go to Sleep

Don't Go to Sleep![[Goosebumps 38] - The Abominable Snowman of Pasadena Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i1/03/27/[goosebumps_38]_-_the_abominable_snowman_of_pasadena_preview.jpg) [Goosebumps 38] - The Abominable Snowman of Pasadena

[Goosebumps 38] - The Abominable Snowman of Pasadena 43 - The Beast from the East

43 - The Beast from the East 51 - Beware, the Snowman

51 - Beware, the Snowman![[Goosebumps 33] - The Horror at Camp Jellyjam Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i1/03/29/[goosebumps_33]_-_the_horror_at_camp_jellyjam_preview.jpg) [Goosebumps 33] - The Horror at Camp Jellyjam

[Goosebumps 33] - The Horror at Camp Jellyjam The New Year's Party

The New Year's Party![[Goosebumps 32] - The Barking Ghost Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/25/[goosebumps_32]_-_the_barking_ghost_preview.jpg) [Goosebumps 32] - The Barking Ghost

[Goosebumps 32] - The Barking Ghost Cuckoo Clock of Doom

Cuckoo Clock of Doom High Tide (9781481413824)

High Tide (9781481413824) Zombie Town

Zombie Town![[Goosebumps 21] - Go Eat Worms! Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i1/03/27/[goosebumps_21]_-_go_eat_worms_preview.jpg) [Goosebumps 21] - Go Eat Worms!

[Goosebumps 21] - Go Eat Worms! Forbidden Secrets

Forbidden Secrets Night of the Giant Everything

Night of the Giant Everything![[Goosebumps 07] - Night of the Living Dummy Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i1/03/28/[goosebumps_07]_-_night_of_the_living_dummy_preview.jpg) [Goosebumps 07] - Night of the Living Dummy

[Goosebumps 07] - Night of the Living Dummy Give Me a K-I-L-L

Give Me a K-I-L-L Ghouls Gone Wild

Ghouls Gone Wild Night In Werewolf Woods

Night In Werewolf Woods The Confession

The Confession The Good, the Bad and the Very Slimy

The Good, the Bad and the Very Slimy It Came From Beneath The Sink

It Came From Beneath The Sink Legend of the Lost Legend

Legend of the Lost Legend First Date

First Date The Dead Boyfriend

The Dead Boyfriend![[Goosebumps 59] - The Haunted School Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i1/03/28/[goosebumps_59]_-_the_haunted_school_preview.jpg) [Goosebumps 59] - The Haunted School

[Goosebumps 59] - The Haunted School![[Goosebumps 11] - The Haunted Mask Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/26/[goosebumps_11]_-_the_haunted_mask_preview.jpg) [Goosebumps 11] - The Haunted Mask

[Goosebumps 11] - The Haunted Mask Halloween Party

Halloween Party Locker 13

Locker 13 Streets of Panic Park

Streets of Panic Park Dudes, the School Is Haunted!

Dudes, the School Is Haunted! 01 - Welcome to Dead House

01 - Welcome to Dead House A New Fear

A New Fear It's Alive! It's Alive!

It's Alive! It's Alive! Don't Stay Up Late

Don't Stay Up Late Stay Out of the Basement

Stay Out of the Basement The Cheater

The Cheater The Awakening Evil

The Awakening Evil Attack of the Jack-O'-Lanterns

Attack of the Jack-O'-Lanterns What Scares You the Most?

What Scares You the Most? 22 - Ghost Beach

22 - Ghost Beach Slappy Birthday to You

Slappy Birthday to You 55 - The Blob That Ate Everyone

55 - The Blob That Ate Everyone 45 - Ghost Camp

45 - Ghost Camp Ghost Beach

Ghost Beach Scream of the Evil Genie

Scream of the Evil Genie Silent Night 2

Silent Night 2 Escape from the Carnival of Horrors

Escape from the Carnival of Horrors 60 - Werewolf Skin

60 - Werewolf Skin Welcome to Camp Nightmare

Welcome to Camp Nightmare The Beast from the East

The Beast from the East![[Goosebumps 61] - I Live in Your Basement Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i1/04/01/[goosebumps_61]_-_i_live_in_your_basement_preview.jpg) [Goosebumps 61] - I Live in Your Basement

[Goosebumps 61] - I Live in Your Basement The 12 Screams of Christmas

The 12 Screams of Christmas The Lost Girl

The Lost Girl Dear Diary, I'm Dead

Dear Diary, I'm Dead Don't Forget Me!

Don't Forget Me! 53 - Chicken Chicken

53 - Chicken Chicken Nightmare Hour

Nightmare Hour Deep in the Jungle of Doom

Deep in the Jungle of Doom Eye Of The Fortuneteller

Eye Of The Fortuneteller![[Goosebumps 14] - The Werewolf of Fever Swamp Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i1/04/04/[goosebumps_14]_-_the_werewolf_of_fever_swamp_preview.jpg) [Goosebumps 14] - The Werewolf of Fever Swamp

[Goosebumps 14] - The Werewolf of Fever Swamp![[Goosebumps 46] - How to Kill a Monster Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i1/04/03/[goosebumps_46]_-_how_to_kill_a_monster_preview.jpg) [Goosebumps 46] - How to Kill a Monster

[Goosebumps 46] - How to Kill a Monster Attack of the Beastly Babysitter

Attack of the Beastly Babysitter![[Goosebumps 35] - A Shocker on Shock Street Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i1/04/04/[goosebumps_35]_-_a_shocker_on_shock_street_preview.jpg) [Goosebumps 35] - A Shocker on Shock Street

[Goosebumps 35] - A Shocker on Shock Street![[Goosebumps 23] - Return of the Mummy Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i1/04/04/[goosebumps_23]_-_return_of_the_mummy_preview.jpg) [Goosebumps 23] - Return of the Mummy

[Goosebumps 23] - Return of the Mummy The Children of Fear

The Children of Fear The Dare

The Dare Say Cheese - And Die Screaming!

Say Cheese - And Die Screaming! 56- The Curse of Camp Cold Lake

56- The Curse of Camp Cold Lake Little Shop of Hamsters

Little Shop of Hamsters Monster Blood IV g-62

Monster Blood IV g-62 Monster Blood

Monster Blood Slappy New Year!

Slappy New Year! 24 - Phantom of the Auditorium

24 - Phantom of the Auditorium 42 - Egg Monsters from Mars

42 - Egg Monsters from Mars 52 - How I Learned to Fly

52 - How I Learned to Fly Temptation

Temptation Party Summer

Party Summer The Scream of the Haunted Mask

The Scream of the Haunted Mask![[Goosebumps 06] - Let's Get Invisible Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i1/04/05/[goosebumps_06]_-_lets_get_invisible_preview.jpg) [Goosebumps 06] - Let's Get Invisible

[Goosebumps 06] - Let's Get Invisible![[Goosebumps 10] - The Ghost Next Door Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i1/04/05/[goosebumps_10]_-_the_ghost_next_door_preview.jpg) [Goosebumps 10] - The Ghost Next Door

[Goosebumps 10] - The Ghost Next Door Goosebumps Most Wanted - 02 - Son of Slappy

Goosebumps Most Wanted - 02 - Son of Slappy Calling All Birdbrains

Calling All Birdbrains Series 2000- Headless Halloween

Series 2000- Headless Halloween Dr. Maniac vs. Robby Schwartz

Dr. Maniac vs. Robby Schwartz Who Let the Ghosts Out?

Who Let the Ghosts Out? Battle of the Dum Diddys

Battle of the Dum Diddys 38 - The Abominable Snowman of Pasadena

38 - The Abominable Snowman of Pasadena 08 - The Girl Who Cried Monster

08 - The Girl Who Cried Monster Don't Scream!

Don't Scream! Visitors

Visitors Werewolf of Fever Swamp

Werewolf of Fever Swamp![[Goosebumps 54] - Don't Go To Sleep Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i2/04/06/[goosebumps_54]_-_dont_go_to_sleep_preview.jpg) [Goosebumps 54] - Don't Go To Sleep

[Goosebumps 54] - Don't Go To Sleep![[Goosebumps 58] - Deep Trouble II Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i2/04/08/[goosebumps_58]_-_deep_trouble_ii_preview.jpg) [Goosebumps 58] - Deep Trouble II

[Goosebumps 58] - Deep Trouble II Werewolf Skin g-60

Werewolf Skin g-60 37 - The Headless Ghost

37 - The Headless Ghost Trapped in Bat Wing Hall

Trapped in Bat Wing Hall Fright Christmas

Fright Christmas Bad Dreams

Bad Dreams Revenge of the Lawn Gnomes

Revenge of the Lawn Gnomes![[Goosebumps 04] - Say Cheese and Die! Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i2/04/07/[goosebumps_04]_-_say_cheese_and_die_preview.jpg) [Goosebumps 04] - Say Cheese and Die!

[Goosebumps 04] - Say Cheese and Die!![[Goosebumps 17] - Why I'm Afraid of Bees Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i2/04/07/[goosebumps_17]_-_why_im_afraid_of_bees_preview.jpg) [Goosebumps 17] - Why I'm Afraid of Bees

[Goosebumps 17] - Why I'm Afraid of Bees The Curse of Camp Cold Lake g-56

The Curse of Camp Cold Lake g-56